Akiba Mashinani Trust

What is AMT?

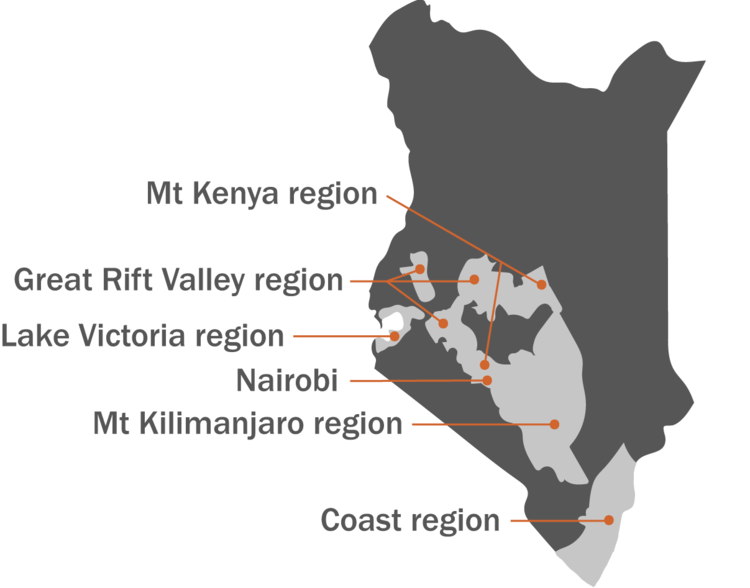

AMT operates through about 30 local Muungano networks that are active in 14 Kenyan counties across 6 regions

Akiba Mashinani Trust is Muungano's finance vehicle, an agency established in 2003 to raise and structure capital in order to achieve community and individual plans.

AMT operates across 14 counties in Kenya. Its primary clientele are women who live in informal settlements.

AMT provides financial and non-financial services to support the many housing, livelihood and other initiatives undertaken by Muungano groups in informal settlements. Through community-led processes, AMT provides access to finance, and technical assistance – including training in financial management, housing development and business management.

One of the main goals of Muungano and AMT is to support collective decision-making and action by the urban poor. Unlike formal banking and microfinance institutions, AMT positions its financial services within a broader effort to improve the physical and social fabric of urban informal settlements.

Why are savings important?

“Shilingi shilingi, nyumba mpya Mathare” – a shilling saved is a new house in Mathare

A Muungano saver's book. Photo: SDI

Savings are critical because they enable wealth accumulation, demonstrate the capacity of the community to repay loans and hence leverage additional resources, and build social capital among members. AMT is able to use these savings as seed capital for revolving funds at the community, city and national scales. The funds offer informal settlers a range of financial products, including community project loans, which allow savings groups to finance social housing, sanitation and basic infrastructure in an affordable way.

The work of Muungano and AMT demonstrates the catalytic impact of establishing appropriate financial services geared towards low-income groups – and how the savings of low-income people can leverage government resources to achieve more inclusive cities.

In addition to savings, AMT resources come from:

- Loan capital: AMT continuously strives to ensure that sufficient sources of capital for loans are in place to fund expected growth

- Donor funds: AMT accesses development assistance from donor agencies.

- Concessional loans: AMT has access to borrowed funds from SDI at a concessional rate.

- Commercial loans: AMT has previously accessed borrowed funds from a commercial bank at a commercial rate

How does AMT work?

Kahawa Soweto savings group, in the late 1990s. Photo: Anastasia Wairimu

AMT is a capital fund which develops financing strategies and products, and raises capital for slum improvement projects such as affordable housing and basic services. It also holds assets such as land and investments for communities – up until the communities are sufficiently organized to hold and manage these themselves. AMT offers deposit and credit services to all residents of informal settlements who are members of Muungano.

AMT's financial services include:

- Savings: these are operated at the group level and include ordinary savings and welfare funds.

- Share capital accumulation: these funds are accumulated at the group level by members and are used for on-lending to members.

- Livelihoods loans: used to finance group enterprise projects or individual projects, such as selling charcoal, groceries, clothes and food, or opening a mobile phone, hotel or motorcycle transport (bodaboda) business.

- Consumption loans: used to cover expenses such as school fees, medical costs and home improvements.

- Community project loans: a credit facility that funds Muungano’s social housing, sanitation and basic infrastructure projects. These are mainly centred on providing affordable and decent housing to Muungano members, or improving basic services in settlements where Muungano members live. These loans finance land acquisition for housing development, greenfield housing development, in-situ slum upgrading and house improvements.

AMT also offers non-financial services like technical assistance to Muungano groups – including training in financial management, housing development and business management. Some training is embedded in the savings process, such as record keeping. Training can also be during group meetings, formal workshops, through learning exchanges between Muungano groups, and in partnership with other organizations.

What difference has AMT made?

“If I want to obtain a loan from the members’ savings, I apply verbally during the group meeting, the members vet my application, and if they approve it the money is issued and recorded by the treasurer at the meeting but I have to pay interest upfront.” (Muungano saver)

Community celebrations for the opening of a new sanitation block in a settlement in Kiandutu settlement in Thika. Photo: SDI

AMT and Muungano support residents of low-income and informal settlements and provide them with opportunities to form strong communal bonds and create shared development goals for their settlements. Community initiatives have also enabled resident to engage constructively with local authorities about strategies to improve quality of life in informal settlements.

- AMT has enhanced inclusion of low-income and other marginalized groups, who have historically been excluded by formal financial institutions. AMT deliberately designs financial services for their benefit, with small sums and simple processes. AMT has represented slum residents in dealings with commercial banks, negotiating changes in the terms and conditions necessary to enable wider access to formal financial services. These financial services complement Muungano's other strategies – such as enumerations and mapping – to ensure no household is left behind. However, AMT cannot always reach those on the lowest incomes. Even with regular savings and flexible financial products, some cannot afford it. This makes strengthening settlement-based community mobilization even more important, as it enables Muungano to identify and ensure people are included.

AMT has promoted participation and accountability within urban communities and financial institutions. Community groups actively manage their programmes through meeting, keeping records, voting as a group on important decisions, and orienting new members. This ensures that AMT’s products and services are locally adapted to suit unique needs of the clients. Savings groups will also elect representatives, who participate in the AMT policy formulation and planning processes.

AMT has developed community capacities to own and manage all service delivery mechanisms, projects and processes. Groups are responsible for all financial transactions at the local level. They bank all funds at their local bank branches. Group rules include clear guidance on managing external & internal resources, incorporating new members, office bearers' and members' responsibilities, attending meetings, and participation in banking activities. In a 2018 study, over 90 per cent of members interviewed understood the contents and significance of these rules.

How is AMT governed?

AMT is governed by a 7-member board, who provide strategic guidance, supervise the finances, manage the organization, participate in institutional planning, approve plans and budgets, receive reports on AMT's performance, and themselves report to various Muungano teams. A majority trustees are drawn from different Muungano communities – this is because AMT holds funds and assets on behalf of slum communities in the Muungano federation – and community board trustees collectively appoint a chairperson from among their number.

AMT has a professional secretariat of 10 staff: an executive director (appointed by the board), 2 finance officers, and 7 field officers distributed across the regions where AMT operates. Field officers help deliver financial and non-financial products to Muungano members, particularly by building local grassroots facilitators' capacities. Staff facilitators train existing groups, mobilize new groups, process and recover loans, file reports, and communicate new information to communities.

Through Muungano's affiliation to SDI, AMT is linked to many African, Asian and Latin American countries with comparable levels of urban informality and income disparities. By extension, AMT represents an increasingly global way of accessing finance connected to urban development. Local funds like AMT are called Urban Poor Funds – the unique and distinguishing characteristic of which is the involvement of beneficiaries in their management. In the Kenyan case, the savings groups of Muungano act as intermediaries between AMT and individuals.

Case Studies

Case study 1: Securing commercial loans – the Sisal Saving scheme

Mukuru sisal village (centre left). Source: Google maps

In 2007, the leaders of Sisal Saving Scheme approached AMT and asked for assistance to purchase a 23-acre plot of land in Mukuru, at a price of KSh 81 million (US$ 777,600). The land had been used by its current owners as security for a loan issued by Eco Bank. Unfortunately, the corporation that owned the land had failed to repay its loan and was now attempting to forestall the bank’s sale by selling the land to settle its debts.

Given the high cost of the land, AMT challenged the leaders to mobilize at least 2,000 savers and to raise at least 20 per cent of the purchase price. Within three months, the group mobilized about 500 savers, who in turn saved about KSh 6 million (US$ 57,600). The Mukuru savings group leaders continued to actively recruit savers to the scheme, and eventually the group had 2,200 members with very robust savings.

Once the group saved the 20 per cent cash collateral, AMT sought to raise the remaining amount to purchase the land. As the trust did not have sufficient funds, AMT’s only viable option was to approach commercial banks for a loan. The banks proved very keen and were impressed by the excellent savings history of the Mukuru group savers. Each bank requested the group to transfer its savings account and to deposit the members’ savings with them. The banks also offered the savers micro loans to improve their businesses.

However, none of the banks was willing to issue a loan to AMT for the purchase of the land. This was because:

- Banks were wary of transacting business with a large group of slum dwellers, due to perceived organizational risks of dealing with such a large group. The banks proposed instead that the members be organized into small groups of five, which could then receive individual loans directly.

- The banks did not have products for large, middle- or long-term loans for low-income earners. The only loan product available for the poor was a short-term micro loan, for business or livelihoods purposes.

- The banks indicated that they could not use the Mukuru land as collateral, as the reputational risk was too high in the event of a default leading to a forced sale. Consequently, AMT as the borrower would have had to secure any loan issued with a cash guarantee and a charge over the land (additional pledged security). Despite these impediments, AMT eventually obtained a five-year loan for KSh 55 million (US$ 528,000) from Eco Bank, which already held the mortgage on the land in question. A condition of the loan was that AMT would secure the property with a charge, and further provide the bank with a cash collateral of KSh 24 million (US$ 230,400), which the bank would hold in lieu in an interest-earning account. The interest on the loan was agreed at the base rate plus 1.5 points. At the time, the bank base rate was 15 per cent a year.

About a year into the loan, the base rate had risen to a staggering 25 per cent. This created a real risk of default for the Sisal Saving Scheme. In response, AMT negotiated for the bank to use the cash guarantee as part of the loan repayment. This, together with the savings from the group, enabled AMT to complete

its loan repayment before the loan completion period. This experience underscored the importance of negotiating creative and mutually satisfactory strategies to reduce financial risk.

Case study 2: Greenfield housing development – the Nakuru West network

Nakuru West savings group meeting. Source: KYC TV

The Nakuru West Network was created in 2002 and has 612 members organized into eight large savings groups. About two-thirds of the members are female market traders who work in the same locality. Almost all the members are tenants who rent poor-quality, temporary houses in nearby informal settlements. On average, members from the networks earn monthly incomes of KSh 13,000 (US$ 124.80). The average rent for a single-room house was KSh 3,000 (US$ 28.80) per month as of 2016, which had increased from KSh 1,000 (US$ 9.60) only three years prior.

The savings groups had a strong credit history with AMT: over two years, they received KSh 4.5 million (US$ 45,000) in consolidated small livelihood loans. These small loans have helped the members of the Nakuru West Network to increase their earnings, strengthen their systems, and build their confidence to take on bigger projects such as the purchase of land and the construction of houses.

To date, the Nakuru West Network has used members’ savings to buy 8 acres of land for 230 members. When members of a group decide to purchase land, they inform their network. A committee is then selected to scout and identify suitable land. After a search of the title has been conducted, the interested members visit the land and decide whether they are comfortable relocating to the area. If the members are happy with the site, the network project committee is given the mandate to negotiate the purchase price and verify the authenticity of the title (with the help of the AMT officer serving the group). In order to ensure affordability, the groups ordinarily ensure that an individual plot will not cost more than KSh 62,400 (US$ 599).

The parcels of land bought by the network are acquired in phases due to the lack of sufficient capital to accommodate all the savers at the same time. Priority is ordinarily given to those members who have saved enough money to complete their portion of the purchase while the rest continue to save for the next phase. After purchase, the network hires a surveyor, who demarcates the land based on its acreage and the number of beneficiaries who have contributed to the purchase.

Once the network purchases land, plots of equal size are then carved from the original title. The groups work with various professionals to envisage their new neighbourhood and determine what type of house they can afford. These discussions determine the design of the houses. The members of the Nakuru

West Network opted for two-bedroom homes of 63.6 square metres. Procurement and construction are overseen by a project team elected by the network, which must source at least three quotations for each item. A separate team is responsible for auditing the project.

The Nakuru West Network has worked with Muungano to construct 52 houses for its members. The savers are required to raise 20 per cent as cash collateral, while the remainder is financed through low- interest loans from AMT. The houses are developed incrementally to reduce the amounts of individual loans. The minimum requirement is that the loan must cover the costs of a foundation and at least one room, so that the saver’s family can relocate to its own house, thus freeing it from paying rent.

This incremental approach means that housing loan repayments are relatively low, ranging from KSh 100,000 to KSh 250,000 (US$ 960 to US$ 2,400). The repayment for a KSh 100,000 loan is relatively low at KSh 1,413 per month. Repayment rates of the Nakuru Network housing loans are presently about 85 per cent. The construction of these initial houses has created great demand from other members working hard to save money for new houses.

Case study 3: Upgrading informal settlements – the Ghetto Housing and Land cooperative

Ghetto house-building. Source: UPFI

The informal settlement of Ghetto is situated on public land in Huruma, in Nairobi County. It has a population of about 550 households. Most of the adult residents of Ghetto are low-income earners who own and operate small-scale businesses. Some of these residents are organized into the Ghetto Housing and Land Cooperative. Many joined the group in 2000 when Muungano was mobilizing residents of Huruma informal settlements who were faced with the threat of eviction. Muungano eventually succeeded in stopping the evictions.

As a response to poor living conditions and the constant threat of eviction, the residents of Ghetto decided to come together with their counterparts in other informal settlements to lobby the county government to upgrade their settlements. In 2003, Ghetto was one of six informal settlements that were set aside for upgrading by the city government. The county government entered into a memorandum of understanding with the residents, in which it consented to release the land to the residents free of charge. For their part, the residents agreed to redevelop the area with the assistance of professionals.

Construction began in 2011 and so far 34 units and 6 foundations have been constructed. The project will eventually benefit 500 households. Before they can secure a housing loan, the beneficiary must be an active participant of the savings group (i.e. attend meetings and save regularly), their household must have been enumerated, and they must have saved 20 per cent of the cost of the house. A major impediment

to housing provision has been the low savings rates (a function of low incomes), making it difficult for households to raise the 20 per cent cash collateral. A second impediment has been those whose housing arrangements differ from most residents: structure owners with lots of rooms for rent, who typically want more than one house during the upgrading process; people from outside Ghetto who buy structures in the settlement for the sole purpose of renting them out; and temporary residents such as short-term tenants. Persuasion and negotiation with these groups, encouraging them to adopt the housing arrangements envisioned under the MoU, is an ongoing activity.

Housing development in Ghetto is carried out in manageable phases of between 20 and 50 units. Like the savers of the Nakuru West Network, the residents of Ghetto work closely with a team of professionals to develop their house design and settlement layout. The typical house design chosen by Ghetto residents is ordinarily incrementally built in three phases. The first phase of construction is normally a starter unit that comprises a ground floor with a shower and toilet on the upper floor. The ground floor space has a footprint of 19.36 square metres and is commonly used as a kitchenette and living area. The total floor space of the starter house is 22.5 square metres. In order to accelerate housing provision, the project teams have moved from constructing starter houses that cost KSh 250,000 (US$ 2,400) to building foundations only, which cost KSh 60,000 (US$ 576). The 20 per cent deposits for foundations are accordingly lower and more achievable.

Ghetto will also benefit from the Kenya Informal Settlements Improvement Programme (KISIP), which will develop secondary infrastructure that will enable the residents to install lane services and then connect their newly constructed homes to the water and sewerage mains. Electricity connections will also be supplied by the government through a World Bank-financed project. These organizations are still determining how the initial upgrading plans and the new KISIP developments will fit together.

Source: much of the above is adapted from Weru et al (2018) 'The Akiba Mashinani Trust, Kenya: a local fund’s role in urban development' Environment and Urbanization Vol 30, Issue 1, pp. 53 - 66